The indictment against journalist Don Lemon and eight others will likely be dismissed because it hinges on a charge that is viewed as so constitutionally flawed that the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division has never attempted to use it to prosecute interference in a house of worship, legal experts say.

The Jan. 29 indictment alleges that the defendants’ involvement in an anti-ICE protest at the Cities Church in St. Paul violated the FACE Act, which prohibits people from intimidating or interfering with people exercising their constitutional freedom to practice religion. It also charges them with a felony of conspiring to interfere with individuals’ religious rights.

They are due to be arraigned on Friday.

The problem, some former Civil Rights Division lawyers say, is that the section in the FACE Act criminalizing interference at houses of worship fundamentally misstates the rights people have under the First Amendment.

The First Amendment protects individuals’ religious freedom from government interference. But it does not protect them from interference by private individuals, like the protesters and journalists charged in the indictment, they say.

Congress passed the FACE Act in 1994 to address rising concerns about threats and intimidation that women were facing at reproductive health clinics.

Since then, it has only been used by the Justice Department to prosecute people accused of interfering with access to medical care at such clinics — and not at houses of worship — because courts have found that interfering with access to a reproductive health clinic impacts interstate commerce.

The constitutional problems with the law, as related to worshipers, are part of the reason prosecutors have never attempted to use it in a religious freedom case.

It’s also just one in a series of red flags that former Justice Department officials believe could spell trouble for the case and lead to a quick dismissal.

“This is not a legitimate use of the FACE Act. This is wholly outside the core purpose that the law was passed, and I will not be surprised if these cases are quickly thrown out,” said Kristen Clarke, the former Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division.

A Justice Department spokesperson did not respond to questions about the decision to use the FACE Act in this case.

No probable cause and no career prosecutors

From the moment the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division tried to charge Lemon, journalist Georgia Fort, Lemon’s driver and local activists who attended the protest, officials have run into road blocks.

Lemon’s attorney has previously said he was there to cover the event in his capacity as a journalist, whose activities are protected by the First Amendment.

The affidavit in support of the complaint was made by an ICE agent with less than a year of experience. Affidavits in cases like this are usually filed by FBI agents, since they are the ones investigating criminal civil rights violations.

Doug Micko, a magistrate judge in the District of Minnesota, rejected arrest warrants for Lemon and four others on the FACE Act misdemeanor charge and a second felony civil rights charge alleging they conspired to violate the churchgoers’ rights.

He also rejected the FACE Act charge for several others who were arrested, including prominent local activists Nekima Levy Armstrong and Chauntyll Allen, writing “no probable cause” in the margin of the warrants.

“This isn’t a prosecution of First Amendment rights — this prosecution is a violation of First Amendment rights,” Levy Armstrong’s attorney Jordan Kushner told CBS News.

When the Justice Department asked the chief judge to review Micko’s decision, and he was unable to respond as quickly as the department wanted, it asked a federal appellate court to intervene and force the lower court to sign the arrest warrants. That court declined to do so.

In court filings related to the appeal, Minnesota Chief U.S. District Judge Patrick Schiltz also criticized the strength of the evidence against the journalists, noting “there is no evidence” that they “engaged in any criminal behavior or conspired to do so.”

Career prosecutors in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Minnesota, meanwhile, also refused to get involved in the case because they were concerned about the lack of evidence that the defendants had committed a federal crime, a source previously told CBS News.

Despite resistance from judges and career prosecutors, the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division rushed to indict Lemon, Fort, and the co-defendants for violating the FACE Act and for conspiring to interfere with the churchgoers’ religious rights.

The indictment only names politically appointed Justice Department lawyers in the Civil Rights Division.

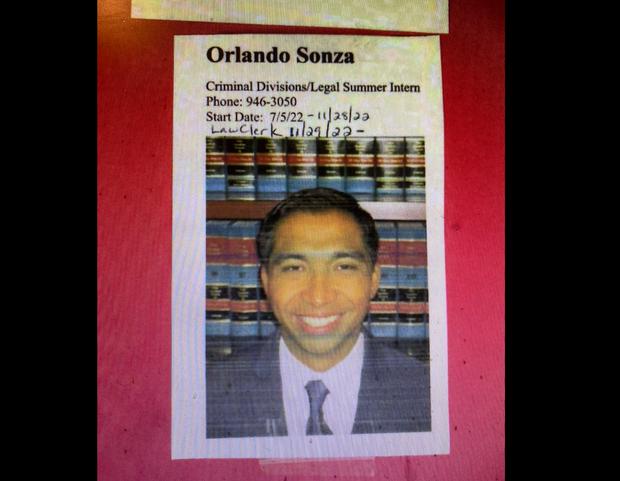

One of the main attorneys assigned to the case — Orlando Sonza — is a failed Ohio Republican congressional candidate who graduated from law school in 2022 and whose only prosecutorial experience until now entailed working in the Hamilton County Prosecutor’s Office over the course of about a year and a half as an intern, a law clerk and assistant prosecutor, according to his personnel file seen by CBS News.

A second Civil Rights Division attorney who was added to the case after the indictment was returned, Greta Gieseke, is also a 2022 law school graduate who is assigned to the Civil Rights Division’s appellate section.

A third lawyer added to the case, Josh Zuckerman, is a 2020 law school graduate who worked as an associate for four years at the multinational law firm Gibson Dunn before joining the Justice Department.

A few hours after CBS News sought comment, Civil Rights Division Acting Deputy Associate Attorney General Robert Keenan, who previously appeared in court during an initial appearance for several of the defendants, formally entered an appearance in the case.

Keenan is a longtime federal prosecutor from the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Orange County, California, though he has not handled many civil rights matters, a review of court filings show.

He was co-counsel on a 2001 color of law prosecution involving two jail employees, one of whom was acquitted at trial, according to court filings and sources familiar with the matter.

Last year, he argued that a local deputy sheriff convicted of civil rights violations in California should have the felony counts struck and should not serve prison time, prompting several of his colleagues to resign.

A few months later, he was dispatched to Louisville to handle the sentencing for a former Louisville police officer who was convicted of violating Breonna Taylor’s civil rights, where the Justice Department recommended the judge to impose a sentence of just one day of imprisonment and three years of supervised release.

“The Department of Justice stands firmly behind the highly qualified attorneys entrusted with enforcing federal law,” a department spokeswoman told CBS News.

She added that Sonza helped convict a defendant in a felony rape trial in Ohio, while Gieseke handled “complex civil and criminal matters” while clerking in federal district and appellate courts.

Keenan, she added, “is a career federal prosecutor with more than 25 years of experience.”

Since the indictment was returned, Magistrate Judge Micko has scolded the lawyers on the case for divulging the details of sealed filings in public court documents, and warned them that future violations “will not be tolerated.”

“When a federal prosecutor makes a decision to charge someone criminally, it is imperative that the Justice Department have a seasoned, sage and experienced prosecutor to vet that process,” said Gene Rossi, a former federal prosecutor. “When politics enters that process, bad things happen.”

One defendant in the Minnesota case filed a motion this week to dismiss the indictment, arguing that it fails to state a federal offense against him.

Uneven enforcement of FACE Act under Bondi

When it was enacted 31 years ago, the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act, or FACE Act, was primarily intended to prevent patients at reproductive health clinics from facing threats as they sought care.

To win Republican support in Congress, GOP Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah extended it to include houses of worship as a compromise with Democrats.

Over the years, the Justice Department has successfully secured convictions against both abortion opponents trying to block access to reproductive health clinics and abortion rights activists.

The reason why that part of the law has proven successful is because courts have found that reproductive health clinics are commercial businesses, and therefore engaged in interstate commerce, said Laura-Kate Bernstein, a former Civil Rights Division prosecutor who handled FACE Act cases.

“There is a wealth of litigation and circuit court decisions holding that the reproductive health aspect of the FACE Act are constitutional,” she told CBS News, noting that health care clinics are “inherently interstate” in how they operate because they receive medical supplies and offer services to out-of-state patients.

A church, however, is typically a local operation that is not engaged in interstate commerce. That and the constitutional concerns have made it untenable to use in any criminal case, she said.

“There really is no interstate commerce clause hook,” she said, noting that the indictment also fails to cite one.

Even as the Justice Department has sought to use the FACE Act as a prosecutorial tool in this case, it has scaled back enforcement in other contexts.

Three days after President Trump took office, he issued nearly two dozen pardons to anti-abortion activists who were charged in FACE Act cases.

The following day, the former acting Associate Attorney General Chad Mizelle ordered the Civil Rights Division to immediately dismiss three pending FACE Act prosecutions involving anti-abortion activists and to cease pursuing any new cases unless they had permission from the head of the division.

Pam Bondi, on her first day as attorney general, ordered the Weaponization Working Group to review prior FACE Act prosecutions during President Joe Biden’s tenure to see if they unfairly targeted conservative Christians.

A review of those cases is still pending and is expected to be conducted, according to one source with direct knowledge of the working group’s plans.

At the same time, however, the Justice Department has allowed FACE Act cases involving protesters at crisis pregnancy centers that discourage abortions to continue without interference.

In one such case, the Justice Department’s career civil rights prosecutors were permitted to proceed with a criminal case in Florida’s Middle District against abortion rights activists who were accused of trying to scare volunteers and workers at a crisis pregnancy clinic that counseled on alternatives to abortion.

The defendant who went to trial was ultimately sentenced to a 120-day prison term in March 2025.

Some former department lawyers say the uneven application of the FACE Act is evidence of the weaponization of the Justice Department against Mr. Trump’s political enemies.

“We have seen across the civil rights statutes that the department enforces the ways in which they have weaponized the use of these laws, not to protect the civil rights of people of this country, but to further their political agenda,” said Johnathan Smith, a former deputy assistant attorney general in the Civil Rights Division.

“I think this use of the FACE Act is consistent with that pattern.”