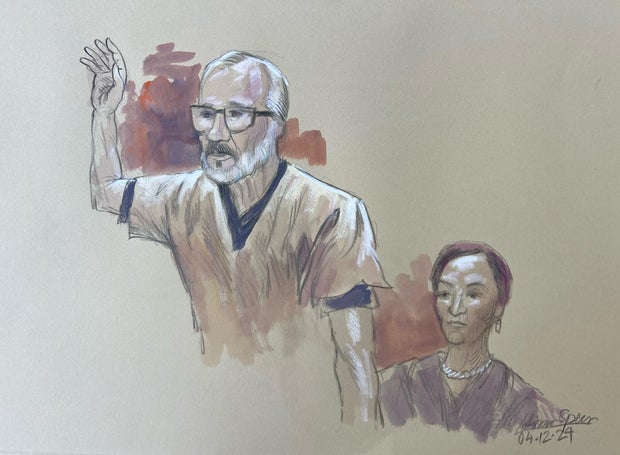

Washington — A former U.S. ambassador formally pleaded guilty Friday to working for Cuba’s spy service for decades and was sentenced to 15 years in prison, bringing a quick end to a case that prosecutors described as one of the longest-running betrayals of the U.S. government in history.

Victor Manuel Rocha, the former U.S. ambassador to Bolivia, was indicted in December on charges that he spied for Cuba’s intelligence agency for more than 40 years. Rocha, who lives in Miami, originally pleaded not guilty in mid-February, then reversed course later that month.

The case’s resolution was briefly in doubt during a hearing on Friday when U.S. District Judge Beth Bloom questioned whether a plea deal Rocha struck with prosecutors was tough enough, since it lacked restitution for possible victims and did not revoke Rocha’s U.S. citizenship. Prosecutors argued that 15 years was sufficient given the 73-year-old would likely die in prison.

The plea deal was ultimately amended to include restitution for potential victims, which will be determined at a later time. Denaturalization is also possible as a civil action down the line.

Rocha also promised to cooperate with the government and provide details about his deception.

“For most of his life, Mr. Rocha lived a lie,” David Newman, a top national security official at the Justice Department, said at a news conference after the sentencing. “While holding various senior positions in the U.S. government, he was secretly acting as the Cuban government’s agent. That is a staggering betrayal of the American people.”

Rocha’s work for Cuba

Little has been revealed about what Rocha did to help the communist regime or how he may have influenced U.S. policy while he worked for the State Department for two decades. He held high-level security clearances that gave him access to top secret information, according to the indictment, which could have made him a valuable asset to Cuba, which has long had hostile relations with the U.S.

But Rocha was not charged with espionage, and instead was accused of acting as a foreign agent, which the Justice Department refers to as “espionage lite.” Acting as a foreign agent carries a shorter prison sentence. Newman suggested the government did not have the evidence to back up espionage charges because there was such a long gap between when the most serious conduct was likely committed and when the investigation began.

Attorney General Merrick Garland has described the case as “one of the highest-reaching and longest-lasting infiltrations of the U.S. government by a foreign agent.”

Born in Colombia, Rocha moved to New York when he was 10 years old after his father died. His family lived with his uncle in Harlem, supported by his mother’s job in a sweatshop sewing factory and food stamps. In 1965, a scholarship to attend Taft School, an elite boarding school in Connecticut, changed the trajectory of his life, he told the school’s alumni magazine in 2004. But while there, he experienced discrimination and considered suicide after his closest friend refused to be roommates with him over the color of his skin, he said.

Investigators alleged Rocha was recruited by Cuba’s spy agency in Chile in 1973 after he graduated from Yale University. That same year, Chile’s socialist president, Salvador Allende, was ousted in a U.S.-backed coup.

He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1978 and also holds degrees from Harvard and Georgetown universities. His career at the State Department began in 1981 and included various positions in Latin America. He briefly held an influential role at the White House National Security Council during the Clinton administration. His career at the State Department culminated in an ambassadorship in Bolivia from 2000 to 2002.

As the ambassador to Bolivia, Rocha warned Bolivians that electing leftist coca farmer Evo Morales, a protege of Fidel Castro, as president would jeopardize U.S. aid to the country. The intervention was credited with helping boost Morales’ standing, and he thanked Rocha for being his “best campaign chief,” the New York Times reported in 2002.

Cuba also fell under Rocha’s purview during his stint at the National Security Council and while he was posted at the U.S. mission in Havana in the 1990s. After leaving the State Department, he was an adviser to the commander of the U.S. Southern Command, whose area of responsibility includes Cuba.

His positions within the government would have given him compartmentalized access to information involving Cuba, including U.S. assessments of the Cuban regime, biographic profiles, details about covert programs run by the U.S. and diplomatic reports from across the world about the Cubans, according to John Feeley, a former U.S. ambassador to Panama who once considered Rocha a mentor.

“He would have been enormously valuable to them,” Feeley told CBS News.

The State Department and the intelligence community are assessing the possible damage to national security, State Department spokesman Matthew Miller told reporters after Rocha’s arrest. The damage assessment is still ongoing, prosecutors said Friday, adding that it would be a “lengthy process” and that they may never know the full harm caused.

An attorney for Rocha, Jacqueline Arango, did not return a request for comment.

“The shock is complete”

Details about how the FBI began to suspect Rocha had acted as a covert agent for Cuba are unclear, other than it received a tip before November 2022, according to court documents. In the following months, the agency surveilled Rocha as he met with an undercover FBI agent whom he believed to be a representative of Cuba’s spy agency.

On Nov. 15, 2022, the undercover agent sent the retired diplomat a WhatsApp message “from your friends in Havana,” the documents said.

“I know that you have been a great friend of ours since your time in Chile,” the undercover agent told Rocha in a subsequent phone call. The two agreed to meet in person the next day.

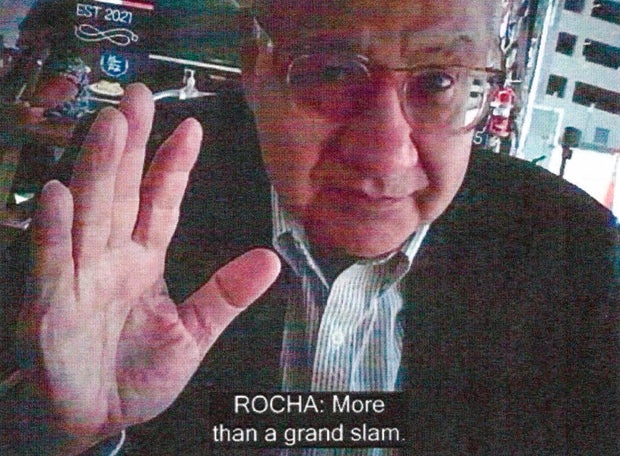

During their conversations over the next year, Rocha referred to the U.S. as “the enemy” and said “what we have done” was “enormous” and “more than a grand slam,” court documents said.

“My number one concern; my number one priority was … any action on the part of Washington that would — would endanger the life of — of the leadership, or the — or the revolution itself,” Rocha allegedly told the undercover agent.

The complaint also alleged that Rocha met with his Cuban handlers as recently as 2017, first flying from Miami to the Dominican Republic using his American passport, then using a Dominican passport to fly to Panama and onto Havana.

Rocha said Cuba’s spy agency had instructed him to “lead a normal life,” and he eventually created a cover story “of a right-wing person” to conceal his double life, according to the complaint.

Feeley, who worked under Rocha when he was the deputy chief of mission for the U.S. Embassy in the Dominican Republic, said in recent years Rocha became an “over-the-top Donald Trump guy.” The two had kept in touch since their posting in the Dominican Republic, but when Feeley last saw Rocha in 2019, the previously apolitical Rocha had “gone down a Trump-MAGA rabbit hole,” as Feeley put it.

“It was really uncomfortable,” Feeley said, adding that he and his former colleagues never suspected it was a cover. “I’ve already been through the whole cycle of grief here. The shock is complete.”

Feeley resigned as U.S. ambassador to Panama in 2018 over policy disputes with the Trump administration.

Rocha did his job well and was generous with his mentoring, but he also had a strong ego and thought he was smarter than others, Feeley said.

On June 23, 2023, Rocha held his last meeting with the undercover FBI agent at an outdoor food court behind a church in Miami. Prosecutors said Rocha became angry when the agent asked, “Are you still with us?”

“I am pissed off,” Rocha allegedly responded, saying it’s “like questioning my manhood. … It’s like you want me to drop them … and show you if I still have testicles.”

Why did a septuagenarian who had managed to escape detection for decades and had long been retired from government service bite so easily at the FBI’s outreach?

“My feeling is that he felt irrelevant,” Feeley said. “You do something for 40 years, it gives you kind of a sense of purpose, and there’s no gold watch at the end of it.”

The Rocha affair is the latest high-profile penetration of the U.S. government by Cuban intelligence, which is considered one of the most effective spy agencies in the world but its capabilities are often overlooked.

The case was widely seen as a failure for U.S. counterintelligence, and Newman said it’s “a reminder that we face espionage and insider risks from a range of countries.”

“We are of course, laser-focused on the threat from China and Russia. But we know that the espionage landscape is not limited to threats from those countries,” Newman said. “The Cuban government continues to be infiltrating our government and undermining American security.”

Ivan Taylor contributed reporting.