Hope Hicks, who was one of former President Donald Trump’s closest aides for years, is testifying on the stand at Trump’s criminal trial in New York, where prosecutors are asking her about some of the key events at issue in the case.

Hicks was Trump’s top press aide during his 2016 presidential campaign and later served as White House communications director. Prosecutors questioned her about her interactions with Trump, and her knowledge of an alleged scheme to suppress salacious stories that could have damaged Trump’s election prospects.

Earlier in the trial, former National Enquirer publisher David Pecker testified that Hicks had been “in and out” of a 2015 Trump Tower meeting where Pecker, Trump and Michael Cohen, Trump’s attorney at the time, allegedly hatched the scheme to bury stories about Trump, a tactic now known as “catch and kill.”

Hicks said she first heard of the payments to Karen McDougal and Stormy Daniels on Nov. 4, 2016, when a Wall Street Journal reporter sent her questions about the McDougal payment. McDougal was a former Playboy model who received $150,000 from the Enquirer’s parent company in exchange for the rights to her claim that she had sex with Trump.

Hicks also had a front-row seat to one of the most pivotal moments of the 2016 campaign: the release of the infamous “Access Hollywood” tape, a 2005 recording in which Trump is heard saying he could “grab [women] by the p****” and “make them do anything.”

The Washington Post first published the tape on Oct. 7, 2016, just weeks before Election Day. Hicks told the jury about how she learned about the tape shortly before the story was published, and said she was “a little stunned.”

One day later, Hollywood attorney Keith Davidson told the Enquirer’s editor that Daniels, his client, was willing to come forward with an allegation that she had sex with Trump in 2006. Cohen ultimately paid $130,000 in exchange for Daniels’ silence. Prosecutors allege the political fallout from the “Access Hollywood” tape was a major driving factor in the decision to pay Daniels.

Trump is charged with 34 counts of falsifying business records related to reimbursements to Cohen. He has pleaded not guilty and denies having sex with McDougal or Daniels.

Hope Hicks’ testimony

Hicks entered the courtroom slowly, wearing a blue blouse under a black suit jacket. On the stand, she spoke quietly at first.

“I’m really nervous,” Hicks said.

Prosecutor Matthew Colangelo led the questioning. Hicks began by recounting her history of working for Trump, which began when she joined the Trump Organization full time in 2014. Trump began exploring a presidential run the next year. She said she began meeting with him more frequently as the “political work” increased.

“He’s a very good multitasker and a very hard worker. He’s always doing many things at once,” she said. By June 2015, she said she would speak to him almost everyday.

“Everybody that works there in some sense reports to Mr. Trump. It’s a very big and successful company, but it’s really run like a small family business in some ways,” she testified.

Hicks fielded questions about some of the key players in the Trump Organization, including Keith Schiller, Trump’s bodyguard; Rhona Graff, an executive and Trump’s aide; and Allen Weisselberg, the company’s chief financial officer.

Hicks said Trump’s political aspirations became apparent in January 2015, when he traveled to Iowa.

“At some point, you know, I think it was sometime around that first trip, Mr. Trump — I think he might have been joking — said that I was going to be the campaign press secretary,” she recalled. “I didn’t take it very seriously, but eventually I started working so much on the campaign.”

At that early stage, Hicks said there was no formal communications team. She reported to him as press secretary. “It was just me, and Mr. Trump, who’s better than anyone at communications and branding,” she said.

Trump was “very involved” in the campaign’s press strategy, Hicks said: “Mr. Trump was responsible. He knew what he wanted to say and how he wanted to say it, and we were all following his lead. And so I think he deserves the credit in terms of the different messages the campaign put forth.”

She said she first met Pecker, the chief executive of American Media, Inc., during a previous job. Working for Trump, she said she “knew they were friends.” She said she overheard Trump praising Pecker for scathing stories the National Enquirer published about Ben Carson and Sen. Ted Cruz, Trump’s rivals for the GOP nomination in 2016.

Pecker testified earlier in the trial that the tabloid would repackage and skew other outlets’ reporting in the most negative light possible in an attempt to help Trump’s campaign. The story about Cruz falsely suggested his father had ties to Lee Harvey Oswald, President John F. Kennedy’s assassin. Pecker testified he would receive direction on certain stories from Cohen.

The “Access Hollywood” tape

Jumping ahead to October 2016, Hicks described how she became aware that the Washington Post was set to publish the “Access Hollywood” recording. She said she was in her office on the 14th floor of Trump Tower when she received an email from the Post’s David Fahrenthold with the subject line, “URGENT WashPost query.”

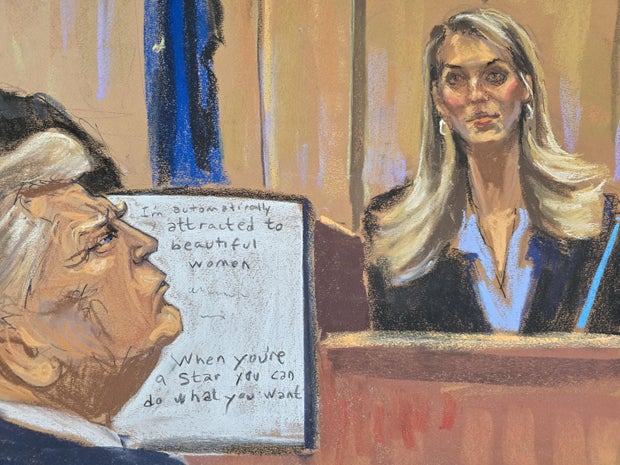

Jurors were shown a transcript of the recording that Fahrenthold included in his email. The judge has not allowed prosecutors to play the tape itself.

She said she forwarded the email to other Trump aides and campaign officials: Jason Miller, David Bossie, Kellyanne Conway and Steve Bannon. She wrote “deny, deny, deny.”

“It was a reflex,” Hicks said on the stand. “I was a little shocked.”

Trump was preparing for a presidential debate in a conference room on the 25th floor. Hicks said she went upstairs and tried to pull aside several other aides. Trump motioned for them to come back in the room, and Hicks read him the email from Fahrenthold.

“We were, at the time, based on the conversation outside the conference room, trying to get a copy of the tape to assess the situation further, and we weren’t sure how to respond yet,” she said. “We were trying to gather information and absorb the shock of it.”

Trump said that the transcript “didn’t sound like something he would say,” according to Hicks.

The Post soon published the story with the recording. Hicks said she was with Trump when he heard it, and that he was upset. Asked for her own reaction, Hicks said she was “a little stunned” and realized it was “going to be a massive story.”

“We were anticipating a Category 4 hurricane making landfall on the East Coast, and I don’t think anyone remembers where or when that hurricane was,” she said.

Campaign officials and Trump himself soon crafted a written statement that was released that afternoon. The statement said the tape was “locker room banter” from “many years ago.” Trump apologized “if anyone was offended.”

Hicks recalled how prominent Republicans quickly denounced Trump over the recording, including Paul Ryan, Mitch McConnell and Mitt Romney.

Two days later, Hicks said she called Cohen “to chase down a rumor I heard from a contact in the media” that there might be “another tape that would be problematic for the campaign.” The rumor ended up being false, but “we sort of chased that down,” Hicks said.

“Is it fair to say that, during this period, Mr. Trump was concerned these reports could hurt his standing with voters?” asked Colangelo, the prosecutor.

“Yes,” Hicks replied.

The Karen McDougal story

Hicks said she didn’t learn about the payments to McDougal and Daniels until Nov. 4, 2016, when she received an inquiry from a reporter from the Wall Street Journal asking questions about McDougal and the National Enquirer.

She said she forwarded the email to Jared Kushner, Trump’s son in law.

“He had a very good relationship with Rupert Murdoch and I was hoping he could buy a little time for us to deal with this,” she said, referring to the Journal’s owner. Kushner said he wouldn’t be able to reach him, according to Hicks.

Hicks said she called Cohen and then Pecker. She said she asked Pecker why she was receiving questions about McDougal, and he explained that AMI paid her for “magazine covers and fitness columns.” Hicks said Pecker told him it was “all very legitimate.”

She worked on a response, sent a draft to Cohen and shared it with Trump. Hicks and Trump called Pecker to confer about their statement to the Journal. The final response included “a denial of the accusations and [said] they were totally untrue.” Hicks said Trump told her to tell the reporter that the allegations were “absolutely, unequivocally” false.

Hicks said the reporter mentioned Daniels on the phone. She said she had heard of the adult actress once before, in November 2015. “Mr. Trump and some of the security guys on the plane were telling a story about a celebrity golf tournament and some of the participants in the tournament, and her name came up,” she said. “She was there with one of the participants that Mr. Trump played with that day.”

Daniels would tell “60 Minutes” in 2018 that she first met Trump at a celebrity golf tournament at Lake Tahoe in Nevada in 2006. She said he invited her to dinner, and she met him at his hotel suite, where they had sex. Trump has denied her account.

The Wall Street Journal published its story about the McDougal payment later on Nov. 4, under the headline, “National Enquirer Shielded Donald Trump From Playboy Model’s Affair Allegation.” Prosecutors showed text messages between Hicks and Cohen in which both of them remarked that few other outlets were following up with stories of their own.

Hicks said she spoke with Trump about the article: “He was concerned about the story. He was concerned about how it would be viewed by his wife. And he wanted me to make sure the newspapers weren’t delivered to his residence that morning.” She added that “everything we talked about in the context of this time period was about whether there was an impact on the campaign.”

The Stormy Daniels story

Colangelo, the prosecutor, moved forward to 2018, when Hicks was serving in the White House as director of strategic communications. Her desk was just outside the Oval Office.

On Jan. 12, 2018, the Journal revealed the $130,000 payment that Cohen made to Daniels for the first time. Sometime in the aftermath, Hicks said she spoke to Cohen, who told her the story wasn’t true.

She said she spoke to Trump about the allegations the next month.

“[Trump] said he spoke to Michael and Michael had paid this woman to protect him from a false allegation,” Hicks recalled. “Michael felt like it was his job to protect him and that’s what he was doing. It was out of the kindness of his own heart.”

Hicks said this would have been “out of character” for Cohen.

“I didn’t know Michael to be an especially charitable person, or a selfless person,” she said. “He’s the kind of person who seeks credit.”

Hicks said the president “thought it was a generous thing to do” and was “appreciative of the loyalty.”

“He wanted to know how it was playing, and just my thoughts and opinion about this story versus having a different kind of story before the election had Mr. Cohen not made that payment,” she remembered. “I think Mr. Trump’s opinion was it was better to be dealing with it now, and it would have been bad to have that story come out before the election.”

Hicks appeared to begin crying as Colangelo turned things over to the defense team for cross-examination. The judge ordered a five-minute break so Hicks could collect herself.