LAKELAND, Fla.—They didn’t need to chase this storm, hunt this hurricane, it was already there—bigger and badder than anything seen before at this time of year, this far out in the Atlantic.

Cmdr. Brett Copare knew he was flying into history on June 30 as he steered the P-3 Orion “Kermit” nose-first into a churning wall of towering thunderheads ringing a 450-mile maelstrom that was but a radar flyspeck 48 hours earlier.

“Before we got out there, it was already a Cat 4,” he said, recalling being “awe-struck” and thinking, “A storm this big, this fast … this is unique.”

That flight of unwelcome discovery was one of dozens made by National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) aircrews in tracking the Atlantic’s first-ever June category 4 and 5 hurricane as Beryl launched its 6,000-mile, two-week romp from Cabo Verde to Vermont.

On his third day of standby July 11 at NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center (AOC) at Lakeland Linder International Airport in central Florida, Cmdr. Copare pondered lessons learned—and questions raised—by a storm that “happened so fast,” and was unlike any of the 25 hurricanes he’s flown through.

“Typically, when storms form, we see them when they are at their lowest status, a low-pressure disturbance, and monitor as they gear up,” he said. “This was the reverse of what we normally observe.”

On this haze-gray day, technicians calibrate instruments inside two Lockheed WP-3D Orions—modified U.S. Navy submarine chasers—parked on the tarmac under a gauzy sun.

Inside the AOC’s hangars, mechanics tend to a Gulfstream G-4 and De Havilland Twin Otter while in offices above, meteorologists and scientists ferret through data from storms’ past and monitor National Hurricane Center radar for storms to come.

All are set to go at a moment’s notice. And after Beryl’s rapid intensification, all are aware that notice could come any moment.

“Currently, there’s nothing out there,” NOAA meteorologist and flight director Sofia de Solo said. The lull comes after she flew three G-4 Beryl missions in 10 days.

“As meteorologists, our job doesn’t end when a mission is completed,” Ms. De Solo said, explaining there’s data to review, instruments to fine-tune, and quality control systems to analyze.

But while she “wouldn’t say it’s boring,” standby is not what she says she’s here to do—that being, ride “a scientific laboratory in the sky” to collect real-time data to save lives.

(Top) A hurricane specialist inspects a satellite image of Hurricane Beryl at the National Hurricane Center in Miami on July 1, 2024. (Bottom) Stickers of previous hurricane missions adorn the side of “Kermit,” a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration WP-3D Orion hurricane hunter aircraft, at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in Arlington, Va., on May 9, 2017. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images, Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images)

From 45,000 feet above, with horizons hemmed only by the planet’s curved roll, storms are disembodied blots spilling across sky blue, sky black, shimmering as “a very bright big white glow,” a pulsating, living literal ball of energy, Ms. De Solo said.

It’s her “dream job” and there’s no place she’d rather be, she said with the derring-do expected of NOAA’s heralded Hurricane Hunters, the fearless pilots and crews who fly into the eyes of hurricanes.

“We’re prepared. It’s going to be a busy year,“ Ms. De Solo said. ”We’re ready to fly.”

Checking her phone for National Hurricane Center alerts, it’s as if she’s alerting the center: “We’re standing by. We’re ready to go.”

Many NOAA Missions

The Hurricane Hunters are the stars, but not the only operators at NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations, which moved from MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa to its custom-built Lakeland AOC in June 2017.

On any day, half the AOC’s 20 pilots, 90 scientists and technicians, two dozen mechanics, and 10 aircraft could be tracking tropical depressions in the Caribbean, mapping coastal estuaries, measuring Rocky Mountain snowpack, or flying for the National Geodetic Survey’s GRAV-D project “calculating the intensity of gravity.”

Most crews are NOAA civilian employees or contractors, but pilots are members of NOAA’s Commissioned Officer Corps, the smallest of eight U.S. federal uniformed services.

NOAA Corp’s 320 officers—there are no enlisted ranks—man 15 research/survey ships and fly specialized data-collecting aircraft, such as those housed at the Lakeland AOC.

A Department of Commerce agency, NOAA coordinates storm-tracking with C-130 “Hurricane Hunter” flights by the U.S. Air Force’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, based in Biloxi, Mississippi.

Like many Hurricane Hunter pilots, Cmdr. Copare is a former military aviator. Before transferring to NOAA, he flew Navy “long leg” surveillance/antisubmarine P-3s.

Entering his fourth season, he’s tallied at least 140 “hurricane penetrations, or “pennies,” he estimates, piloting Orions older than their crews straight into storms beginning with Cat 4 Hurricane Ida in 2021.

(Top) “Kermit,” a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) WP-3D Orion hurricane aircraft, is displayed at the Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in Arlington, Va., on June 3, 2024. (Bottom Left) Inside the cockpit of “Kermit”. (Bottom Right) An interior view of the NOAA’s Gulfstream IV jet at the NASA Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla., on June 25, 2024. (Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images, Miguel J. Rodriguez Carrillo/AFP /AFP via Getty Images)

NOAA’s two P-3s—their fuselages festooned with Kermit and Miss Piggy stencils personally crafted by Muppeteer creator Jim Henson—have flown through more than 100 hurricanes since 1976.

During eight-to-10-hour missions, their 18-to-20 member crews of three pilots, navigators, engineers, technicians, and flight meteorologists, are locked into “Setting 5” work-station harnesses, chart air chemistry, barometric changes, wind speeds, temperature shifts, updrafts, downdrafts, and all the mayhem between in real-time transmit to the National Hurricane Center.

Much data is collected by dropwindsondes, Pringles can-shaped probes that measure wind, temperature, humidity, and pressure as it parachutes through a storm.

Ms. De Solo said she deploys about 30 every mission aboard “Gonzo,” the G-4 also sporting an original Henson stencil.

While crews collect data, pilots plot the storm’s track by flying Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) patterns, or “quadrant-to-quadrant butterflies and circle-eights,” Cmdr. Copare said.

“We start at one corner of the storm, make three to four passes through the core,” he said. “Then, back in. The aim is to find the center path by dead reckoning, each fix to each fix.”

Each “penny to penny” pass at 8,000-to-10,000 feet can take an hour with P-3s usually making three to four every mission.

NOAA provides simulations and training, but replicating a flight through a 120-mph slipstream of fury in a careening canister is hard to do.

“There’s really no way to prepare yourself for what that’s going to be like,” Cmdr. Copare said, noting as the battered plane bounces and heaves, there’s an out-of-body sense with the windshield obscured by rain, all sound blurred in a thunderous, rattling roar, and two-handed focus on cockpit controls.

He recited the mantra repeated since a B-25 Mitchell bomber crew first successfully flew through a hurricane in 1943 because it’s still the best way to describe it.

“It’s like riding a roller coaster through a washing machine,” Cmdr. Copare said.

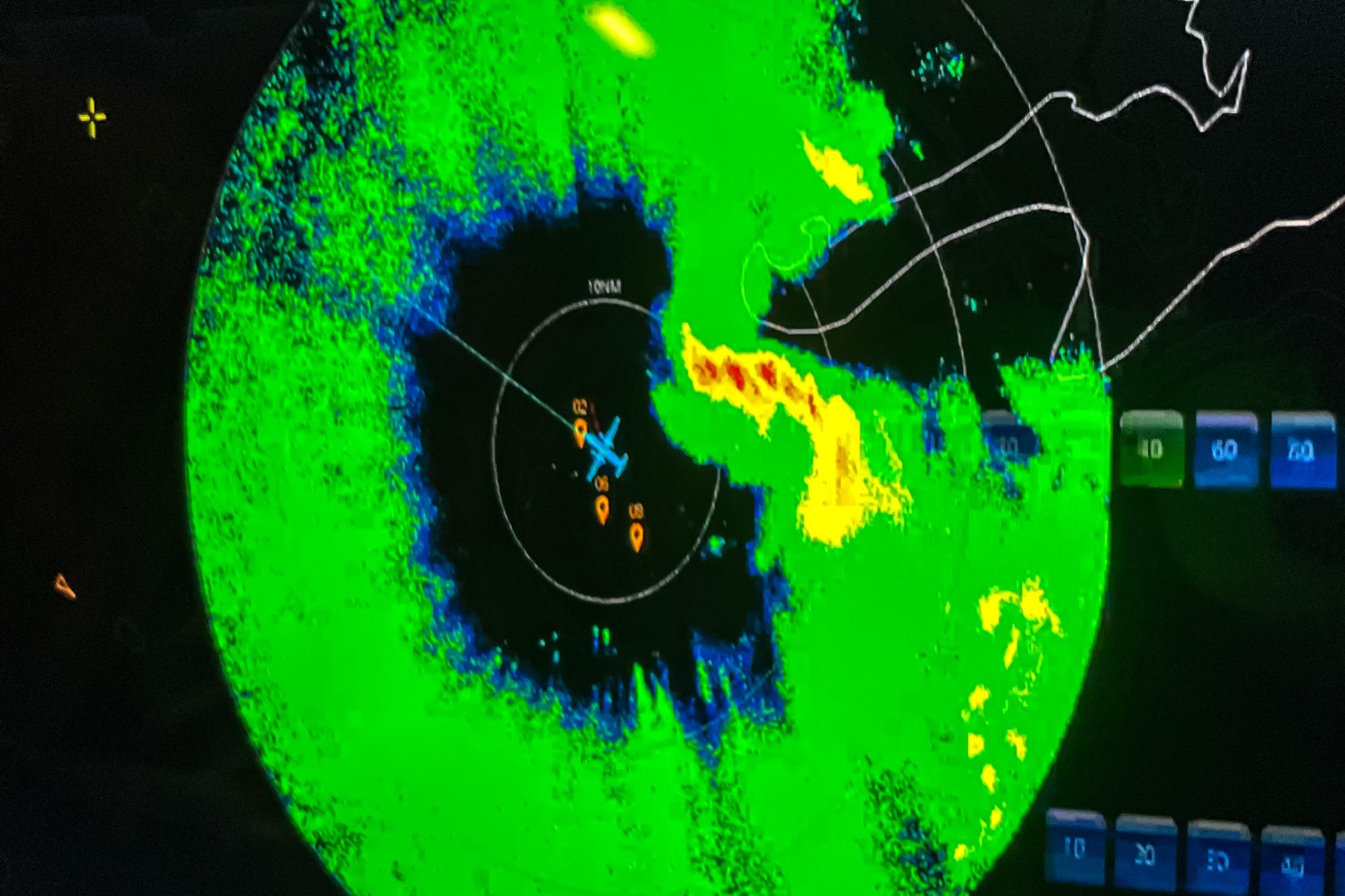

(Top) The NOAA’s dropsondes meteorologic system at the NASA Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla., on June 25, 2024. (Bottom Left) A flight director operates a work station on NOAA WP-3D Orion N43RF aircraft, “Miss Piggy” during a flight to Hurricane Lee on Sept. 8, 2023. (Bottom Right) A radar display from “Miss Piggy” in the center of circulation of Hurricane Idalia off the western coast of Cuba on Aug.28, 2023. (Miguel J. Rodriguez Carrillo/AFP /AFP via Getty Images, NOAA Corps)

And then, the eye—a sudden, still, soundless void where the “wind goes from 150 knots to zero, everything goes from super loud to still silence, to an eerily peaceful feeling,” he said.

“It’s an awe-inspiring thing, flying into the eye of a well-developed hurricane,” Cmdr. Copare said. ”Just looking around and seeing … it’s a stadium effect.”

Later, on the ground, it hits. “You land and it’s like a high, you realize you just flew into a hurricane,” he said.

Some Come Running

On the G-4, Ms. De Solo is checking Gonzo’s Airborne Expendable Bathythermographs supply. They measure ocean temperature, providing a “structure of a storm” and a gauge of its intensity.

A Miami native fascinated with tropical weather since childhood, she has a Bachelor of Science in meteorology from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and a Masters in professional meteorology and climatology from Mississippi State University.

Ms. De Solo worked in NOAA’s National Weather Service in Key West, Florida, for about a year before transferring into the Hurricane Hunters as a flight director or “the meteorologist on board.”

She spends winters with Gonzo in Hawaii tracking “atmospheric rivers” across the Pacific.

She keeps track of flight hours on a spreadsheet but doesn’t count them. Entering her third season, Ms. De Solo estimates she’s flown “hundreds of hours” observing weather from 45,000 feet.

Like the pilots, she’s an eager volunteer.

“I have fulfilled my childhood dreams of flying into a hurricane,” she said, noting only by being inside the storm can scientists study the storm. “I am living my dream.”

For others, their wildest dreams didn’t include flying into hurricanes.

Austin Roche had no clue he’d be buffeted and bounced by geyser-like updrafts in a Gulf Stream pressed against the ceiling of the sky when hired as lead G-4 aircraft mechanic.

“I fly with the plane anywhere it goes,” he said, including right into Cat 5 storms. “It’s like a roller-coaster without the tracks” except, he added, that’s “absolutely not even close” to what it’s really like.

NOAA meteorologist and G-4 flight director Sofia de Solo sits in an instrument station aboard “Gonzo,” where technicians and scientists document storms from 45,000 feet above the planet. (The Epoch Times/John Haughey)

NOAA media specialist T.J. Iddings, who worked as an Orlando TV meteorologist before joining NOAA last year, is also among ground staffers accruing “pennies.”

He flew through Beryl to capture film footage before it barreled across Yucatan. “It’s definitely quite an experience,” he said of his first time flying through a hurricane’s eye.

“I really like it—it’s growing on me,” Mr. Iddings said.

In the AOC’s sheet metal shop, Edgar Serrano and his jack-of-all-trades team aren’t flying off anywhere. It’s their job to ensure computers, instruments, and people don’t fly off anywhere inside the planes as they shake, rattle, and roll to “10G crash standard,” he said.

Mr. Serrano said NOAA’s shop technicians “over-design” everything to customized specifications.

He points to thick brackets with large screw holes to keep components attached to bulkheads, triple-brace coffee mug holders, paint that turns to powder, and to an invention he fabricated to the exacting, expressed needs of pilots, crew, and janitors.

“It’s a barf-bag holder,” Mr. Serrano beamed, holding what looks like a reinforced metal creel with a flip top and sturdy, square hold that can be mounted by screw-in braces.

“They get used?” he laughed, confirming a gut-wrenching truth. “Oh yeah, yeah they do.”

Original News Source Link – Epoch Times

Running For Office? Conservative Campaign Consulting – Election Day Strategies!