What happens at the Republican National Convention, being held this week at Milwaukee’s Fiserv Forum, will help determine whether Donald Trump – whose vision of America differs sharply from that of President Joe Biden – will return to the White House. But it was a much smaller meeting, in a much smaller town about 90 miles away, that proved every bit as consequential.

On March 20, 1854, around 50 concerned citizens gathered inside the Little White Schoolhouse in Ripon, Wisconsin, widely believed to be the birthplace of the Republican Party. “These were people who wanted to form a new party,” said Russell Blake, a history professor emeritus at nearby Ripon College. “They were a combination of merchants, farmers, lawyers. It was a town that was only four, five years old. People had only recently moved here.”

And all of them were alarmed by the prospect of slavery spreading westward. “They believed that the nation had been founded on the supposition that slavery would eventually disappear – they really did believe in what they called a free society,” Blake said.

But earlier that same year, Congress had introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act, allowing settlers in those territories to decide whether slave-holding would be permitted. The earlier Missouri Compromise had prohibited slavery in those areas. For anti-slavery Americans like the ones meeting in Ripon, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was a profound betrayal. The Ripon Herald newspaper, in March 1854, denounced the bill as a “nefarious scheme.”

Historian Richard Brookhiser, senior editor at the National Review, said it fueled outrage at the existing political parties: “The old parties had failed, and there needed to be some new force in American politics,” he said, calling the Kansas-Nebraska Act the kind of “earthquake” needed to start a new major party.

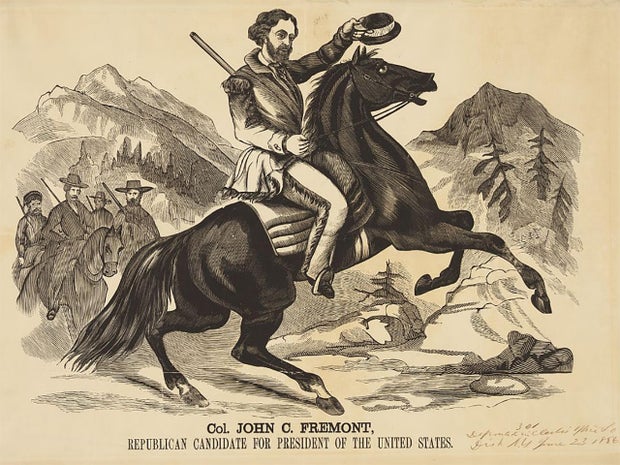

Ripon wasn’t the only place where citizens were mobilizing. Ordinary Americans who felt politically homeless were meeting throughout the North. The movement grew so quickly that in 1856 the Republicans fielded a presidential candidate, John Frémont, who came very close to winning, with 114 electoral votes compared to winner James Buchanan’s 174 and Millard Fillmore’s 8. “You compare it to other third parties – Ross Perot, or George Wallace, or the Libertarians – no one has had a debut like that,” Brookhiser said.

Just four years later the Republicans’ second candidate for president, Abraham Lincoln, went all the way.

For nearly 70 years after the Civil War, the GOP dominated the White House. Only two Democrats – Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson – won election during that span.

That run came to a crashing halt in the early 1930s.

“The Great Depression practically eliminates it for a while,” Brookhiser said. “Hoover is president when the bottom falls out of the stock market, and Roosevelt wins in a landslide in 1932. After World War II, there is a competitive two-party system once again.”

So, who makes up the Republican Party today? “Donald Trump, and those who admire him,” Brookhiser said. “That’s the short answer.”

“That sounds like a party shaped by a single person,” said Rocca.

“It is.”

Asked if the earliest Republicans would recognize today’s GOP, Blade said, “Probably not. I think they would be surprised at the corporatization of America in general, whether that’s represented by Republicans or Democrats. Theirs was a world in which everything was on a small scale. The idea of large corporations, like the idea of large slave plantations, probably would have made them nervous.”

So, where might the party be in ten years’ time? Brookhiser said, “I don’t think either party will implode. I think they’ve been around too long. There’s too much infrastructure, so to speak. When Trump retires or steps down, there’ll be plenty of Republicans who are officeholders who’ll be lookin’ after number one.”

For more info:

Story produced by Michelle Kessel. Chad Cardin.