We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

In the twenty-three years since he left the White House, former President Bill Clinton has worked to refashion a life of politics as a public servant and elected official, into that of a private citizen aiming to advance the promise of America, at a time when there was emerging, in his words, “Two Americas … with very different stories.”

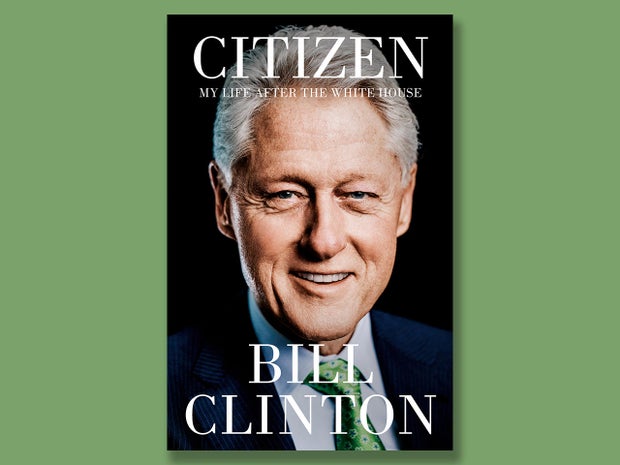

In his new book, “Citizen: My Life After the White House” (to be published Tuesday by Knopf), Clinton considers the post-presidencies of other chief executives, from John Quincy Adams to Jimmy Carter, and how he himself is determined to “live in the present and for the future.”

Read an excerpt below, and don’t miss Tracy Smith’s interview with Bill Clinton on “CBS Sunday Morning” November 17!

“Citizen: My Life After the White House” by Bill Clinton

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

On January 21, 2001, after twenty-five years in politics and elected office, eight as president, I was a private citizen again. I often joked that for a few weeks, I was lost whenever I walked into a room because no one played a song to mark my arrival. “Hail to the Chief” was now my successor’s anthem. I had loved being president, but I supported the two-term limit and was determined not to spend a day wishing I still had the job. I wanted to live in the present and for the future. Except on rare occasions, I have kept that promise to myself, though it got a lot harder after the 2016 election, harder still after the coronavirus struck, George Floyd’s killing, the January 6, 2021, attack on our Capitol, and the inventive efforts of the right-wing culture warriors to find new ways to stoke grievances without sensible plans to make things better for themselves and for all the rest of us.

The years after the White House are different for every former president. In 2001, I was only fifty-four, with a lot of energy, useful experience, and contacts from my years in politics that could and should be used to serve the public as a private citizen.

So how should a former president do that? Several of my predecessors had made a real difference in their time, disproving John Quincy Adams’s famous maxim that “there is nothing more pathetic in life than a former President.” Adams himself served sixteen years in Congress, two of them with Abraham Lincoln, where he led the fight against slavery on the floor of the House. He also represented the captive African Mende people aboard the Amistad in the Supreme Court, winning their release before they could be sold into slavery. Theodore Roosevelt started a new party and ran for president, finishing second in 1912, the only third-party candidate to do so. William Howard Taft became chief justice of the Supreme Court. Herbert Hoover led an effort to modernize and reorganize the federal civil service under President Harry Truman. And Jimmy Carter built a remarkable record with his foundation, eliminating the scourge of guinea worm in Africa, overseeing elections in tough places, and becoming, along with Rosalynn, the face of Habitat for Humanity.

Although Hillary was now serving in the Senate, I had always been impressed by the impact she had by working with nongovernmental organizations, beginning with the Children’s Defense Fund. And I had learned a lot in our White House years watching her work with civil society groups in Africa, Northern Ireland, India, and elsewhere.

So I decided to set up a foundation with a flexible but clear mission: to maximize the benefits and minimize the burdens of our new century in the United States and across the world. I was excited about the possibilities and hoped I could do it.

Meanwhile, I had a more immediate agenda. I wanted to support Hillary, just starting her service as a senator from New York, and Chelsea, only a few months from graduating from Stanford, so they could stay in public life if they wanted to do so and be financially secure if I didn’t live long, which, given my family history, seemed likely. To do that and pay my substantial legal bills run up during the Whitewater investigations and the impeachment process, I had to start making money, something that had never interested me before. As governor of Arkansas, I had made $35,000 until the voters raised it to $60,000 a couple of months before I left office. As president I made $200,000, and paid for most of our family’s expenses out of it, in large part because the job provided excellent public housing!

By the time I left office, I had given a lot of thought to how to increase the opportunities and decrease the problems of our interdependence. We had to create more fairly shared prosperity, shoulder more shared responsibilities, and build more communities in which our differences are respected, but our common humanity matters more.

But the America that I found myself working in had changed in many ways since I had started in politics in the 1970s, and even in the short time since I’d left the White House. Two Americas were emerging with very different stories. One believes that our diversity makes us stronger, and better able to achieve shared prosperity through shared opportunities and responsibilities and equal treatment in our local, state, and national communities. The other believes they are in a battle for all that has been lost by our increasing diversity and economic stagnation, mostly in more rural areas. They feel they’ve lost control over our economy, our social order, and our culture. They’re determined not to lose control over our politics, and to use politics to regain control over the other three.

I still believe we all do better when we work together. In such a polarized environment, that means you have to be willing to work with people who don’t think like you along with those who do. Almost always, cooperation beats conflict, and when you do have to stand your ground, it’s wise to leave the door open for reconciliation. The ability to do that distinguishes great leaders. Think of Nelson Mandela putting the leaders of parties who had imprisoned him for twenty-seven years in his cabinet, or Yitzhak Rabin keeping the peace process alive while acts of terror claimed the lives of innocent citizens and eventually claimed his.

Following this path is challenging even in less violent times. My family has had a lot of experience with highly personal attacks which were not just hurtful to us, but hurt the country by distracting attention from the real debate: how best to meet our common challenges. When the going got rough, I tried to imagine that I was one of those big inflatable toys of the cartoon figures Baby Huey or Casper the Friendly Ghost—they were big favorites of kids when I was in elementary school. You could knock them down and they always bounced right back up. To survive in politics, that’s what you have to do, over and over. Maybe we should start producing those bouncing figures again, as representative of happy warriors reaching across our great divide. People could keep them at home and at work, starting and finishing every workday by knocking them down and smiling when they bounce back. It might clear our heads and help us to get back in the building and cooperating business.

A life in public service can be deeply rewarding if you accept that in the constant ebb and flow of history there are no permanent victories or defeats, and never forget that every life is a story that, regardless of time and circumstance, deserves to be seen and heard.

As I entered this new chapter of my life, I knew that I’d keep score the way I always have: Are people better off when you quit than when you started? Do our children have a brighter future? Are we coming together instead of falling apart?

This book is the story of my twenty-three-plus years since leaving the White House, told largely through the stories of other people who changed my life as I tried to help change theirs, of those who supported me, including those I loved and lost, and of the mistakes I made along the way.

I’m very grateful that, with the help of my family, friends new and old, a great staff, and the endurance of my curiosity, energy, and ability to work, I have been able to have a life full of new experiences and new ways to help and empower people as a private citizen while finding real joy in our small but growing family. I’ve loved cheering Hillary on as a senator, secretary of state, presidential candidate both in 2008 and in 2016, and watching with wonder the life Chelsea has built with her work in the private sector, in academia, the Clinton Foundation and the Clinton Health Access Initiative, with the books she’s authored, and her family life with Marc, whom I love and admire. Chelsea says she and Marc are teaching their kids to “be brave and be kind.” It shows. I love being their grandfather, and am so glad Chelsea and Marc welcome Hillary and me to be involved in their lives.

When this book comes out, I’ll be seventy-eight—the oldest person in my family since my maternal great-grandparents, straight out of American Gothic, made it into their late seventies. But I still think and dream about how people can live better lives together, and still want to help them do it. I can’t sit still and can’t go back. So, as many people do every day, I aim to get caught trying. It’s the real American way.

Excerpted from “Citizen: My Life After the White House” by Bill Clinton, published by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Bill Clinton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Get the book here:

“Citizen: My Life After the White House” by Bill Clinton

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info: