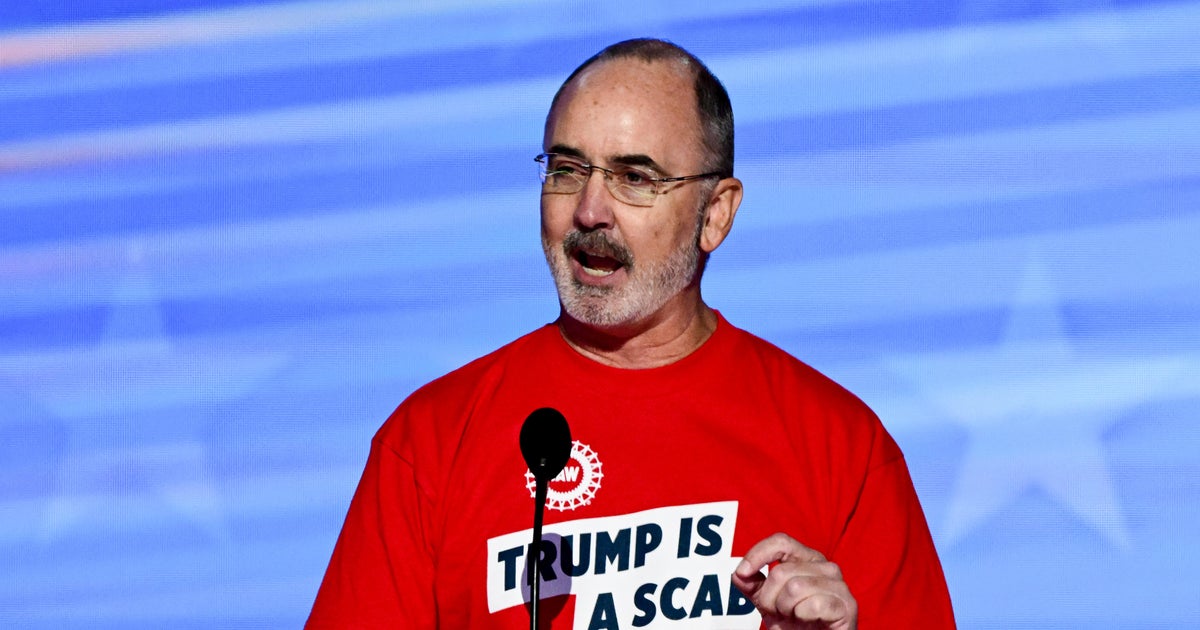

It was one of the most fiery moments of the Democratic National Convention. Last Monday night, Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers union, strode onto the stage at the United Center, took off his blazer and revealed a red t-shirt that read “Trump is a scab.”

The crowd, filled with party faithful who were also wearing the same T-shirt, roared with approval and began chanting “Trump’s a scab.” Fain, an electrician who worked in an Indiana automotive parts factory, is a throwback to the more bare-knuckled archetype of labor leaders. He exalted Democratic nominee Kamala Harris as a “fighter for the working class” and skewered Trump as a “lapdog for the billionaire class.”

But while Fain evoked the combative labor bosses of an earlier era, behind that vintage style was a state-of-the-art, tech-savvy campaign machine poised to capitalize on the moment. Before long, the digital foot soldiers of the Harris-Waltz team, along with the UAW, had plastered the Fain video across social media, garnering millions of views, thousands of the bright red t-shirts had been sold, and the word “scab” was trending online.

That bit of choreographed theater reflected the methodical planning and preparation by the Harris-Walz campaign to find every opportunity to amplify labor’s message and, just as importantly, to burnish its own pro-union credentials with the labor leaders they are aggressively courting. And for good reason — the union vote could be decisive in 2024.

Aware that Donald Trump’s strong performance with union households in battleground states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin may have cost Hillary Clinton the election in 2016, the Harris campaign understands that blue-collar voters may emerge as this campaign season’s version of the suburban soccer mom – a pivotal demographic for victory.

“There are 2.7 million union members in the battleground states,” wrote Julie Chavez Rodriguez, the Harris-Walz campaign manager, in an Aug. 8 memo shared with CBS News. “That means something when roughly 45,000 votes in key states decided the election four years ago.”

Last week, Democratic Party convention planners overlooked no detail in wooing labor. A record number — 20% — of Democratic delegates were union members; all delegation members from the 50 states and territories stayed in union hotels; almost all of the physical work at the convention drew from union labor, from building the sets to the electrical work, as well as the makeup for speakers and performers. And raucous callouts to unions were strategically placed in many of the celebratory roll call votes.

The Harris campaign sees its tight collaboration with labor as a force multiplier.

“We are in a fragmented media environment and it’s very hard to reach undecided voters,” one campaign official said. “Unions are the ultimate validator: they can break through the noise and misinformation and lay out the facts on our record vs. Trump.”

Once a staple of the Democratic Party, labor union members have splintered in the Trump era – with the Republican former president proving effective at drawing those traditional Democratic voters across the aisle. Backstage at the convention hall, it was clear the Harris campaign was employing old-school, hardball tactics to try to counter those gains.

When another prominent union boss, Teamsters president Sean O’Brien, addressed the Republican convention in Milwaukee late last month, Democrats took notice. O’Brien praised Trump as “one tough SOB” and said he “didn’t care about being criticized” for being the first Teamsters boss to speak at a Republican convention in its 121-year history.

But two weeks later, Trump was yukking it up with Elon Musk in a conversation on X about firing workers. The Republican nominee praised Musk as “the greatest cutter,” telling him “look at what you do, you walk in, you say ‘you want to quit?’ I won’t mention the name of the company, but they go on strike, and you go: ‘You’re all gone!'”

O’Brien quickly engaged in damage control, issuing a statement to Politico calling Trump’s remarks “economic terrorism.” But the Harris campaign and its labor allies saw an opportunity for payback. The next day, the UAW’s Fain filed a complaint against both Trump and Musk with the National Labor Relations Board charging them with unfair labor practices. The Harris campaign was delighted and urged Fain to hit the airwaves to talk about their move, according to a source close to Fain.

O’Brien scrambled for an opportunity to get back into the Democrats’ good graces. He asked to speak at their convention, but the Harris campaign froze him out, according to a labor source. Campaign officials didn’t even respond to his request. Then, in a move that appeared to be meant to undermine O’Brien, the Harris campaign invited multiple rank-and-file Teamsters members to participate in the convention festivities without their leader.

One labor source who asked not to be identified in order to speak freely about the episode called it “a snub.” Others suggested it was meant to send a gentle message that there could be consequences for backing Trump.

“They weren’t throwing a ball at his head, but maybe slightly inside to make him take a step back from the plate,” said Eddie Vale, a political and labor strategist who has represented unions including the AFL-CIO. A Harris campaign source simply said that it would not have made sense for O’Brien to address the convention, given that he was not prepared to endorse the Democratic ticket.

And yet, at the close of the convention, officials with Harris’ campaign said they were keeping the door open for a possible rapprochement with the Teamsters leadership. In what one labor source called “virtue signaling,” Harris accepted an invitation to meet with the union’s executive board, which is expected to include O’Brien.

“Both sides want it known that they are continuing to talk to each other,” the source said.

Harris faces a tougher challenge in courting union support than her predecessor. President Biden’s close relationship with unions took shape after years of cultivating his image as “Scranton Joe,” a politician whose middle-class roots helped him understand the plight and aspirations of workers. But Harris, a more cosmopolitan personality from California’s Bay Area, has had to do more work to define herself as a natural ally of the working class.

In 2020, Mr. Biden won 57% of the union vote in the key rust-belt states, compared to Trump’s 40%. Harris, by most accounts, will have to do at least as well as Biden to prevail in this election.

Trump has also been wooing big labor. In January, he participated in the Teamsters Rank-and-File Presidential Roundtable (Mr. Biden visited Teamsters headquarters a few weeks later) and heaped praise on the union, noting that many of his big projects have been built with Teamsters labor. And in a vintage bit of transactional politics, he vowed to give unions leaders a “seat at the table” if they endorse him in the election.

The Harris team is being strategic about its courtship of labor. At last week’s convention, speakers seemed to take every opportunity to point out that Harris had worked at a McDonald’s when she was in college, and the nominee herself also brought it up during her acceptance speech. Harris spoke sentimentally, but tactically, about the modest East Bay neighborhood she grew up in, calling it “a beautiful working-class neighborhood of firefighters, nurses and construction workers.”

And almost as soon as Harris had become the presumed nominee last month, her campaign sent her on a battleground state tour where she met with rank-and-file union members, including UAW workers in Detroit. The campaign has emphasized Harris’ pro-union record, pointing out that she walked the picket line with union strikers in 2019 during her first presidential run and that as vice-president, she broke the tie in the Senate that allowed passage of the Butch Lewis Act, which restored the pensions of more than a million workers.

Then there was Harris’ selection of Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz as her running mate. His plain-speaking Midwestern style, football coach persona and worn flannel shirts represent an appeal to lunch-pail voters. A Harris campaign official said it was no coincidence that Walz’s first solo trip of the campaign was to rally members of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees at their international convention in Los Angeles. And not insignificantly, Walz, a former high school teacher, is himself a card-carrying union member of a union — the American Federation of Teachers.

Ultimately, the labor vote is likely to follow the candidate workers feel can best address the economic of the working class. Harris will almost certainly win the labor vote, but what will really matter is Trump’s ability to cut into her margins with economic appeals to working-class voters, likely on immigration and trade.

Robert Forrant, a historian of the American labor movement, says the Harris campaign recognizes this, and it’s making those economic concerns part of her message.

“They’ve started to talk about how inflation really mattered, and you can’t pretend it doesn’t.” But he said the Harris campaign still needs to do more, like acknowledge that working people have increasingly had to hold down multiple jobs to get by, a reality that has third-order effects, including damaging family structures. “You have to thread the needle when appealing to the union vote,” Forrant said.