The March 4 opinion centralized decision-making with Congress and effectively negated the possibility of multiple, ongoing court battles in states like Colorado.

It also nullified rulings that he was disqualified in Maine and Illinois and removed the disqualification option from state judges, whose decisions could have been used to justify similar moves in other states.

According to the court’s liberal justices, the decision also precluded the possibility of federal courts weighing the disqualification issue.

“It now seems all but certain Trump will be on the November ballot,” University of Michigan Professor Barbara McQuade told The Epoch Times. Ms. McQuade left the Justice Department amid a wave of departures at the outset of President Trump’s administration.

She favored federal legislation disqualifying the former president but noted “that outcome seems unlikely in light of the split of power between the House and Senate.”

Perhaps foreshadowing a rocky campaign cycle, Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the liberal justices in criticizing the extent the majority went in its opinion amid a “volatile” election season.

“In my judgment, this is not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency,” she said. “The Court has settled a politically charged issue in the volatile season of a Presidential election. Particularly in this circumstance, writings on the Court should turn the national temperature down, not up.”

What Does the Supreme Court Ruling Mean?

The Supreme Court issued a per curiam, or unanimous, judgment that states like Colorado cannot rule candidates for federal office disqualified from appearing on state ballots.

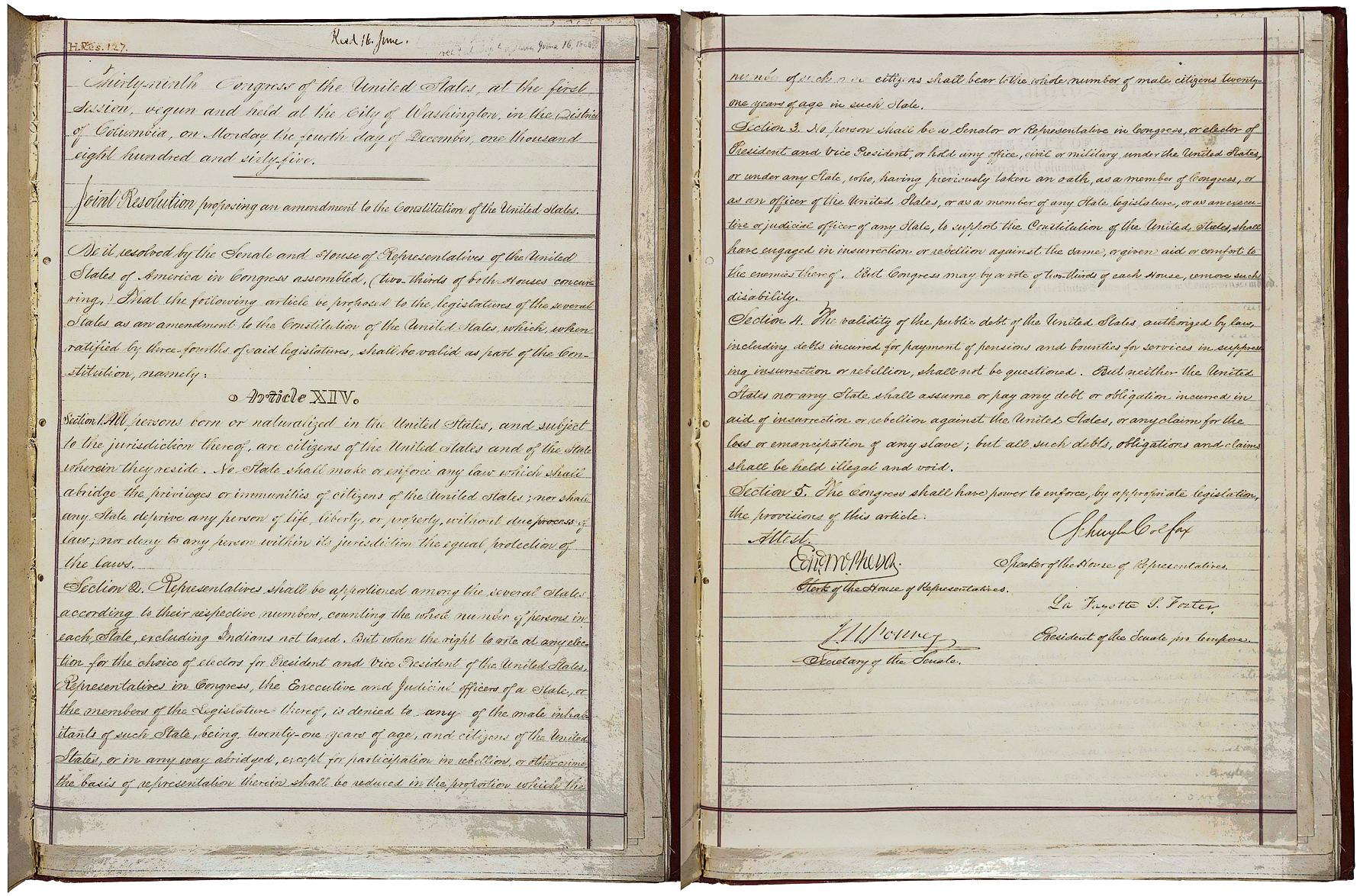

Instead, it drew from the 14th Amendment’s wording to grant that authority to Congress while providing guidelines for acceptable legislation. More specifically, it pointed to the wording in Section 5 of the Amendment, which reads: “The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”

The opinion read: “The terms of the Amendment speak only to enforcement by Congress, which enjoys power to enforce the Amendment through legislation pursuant to Section 5.”

The Supreme Court drew from the 14th Amendment (bottom) to grant Congress (top) the authority to disqualify candidates for federal office. (Samuel Corum/Getty Images, National Archives of the United States)

Going forward, the electoral map is less likely to be the messy “patchwork” that some suggested it would be with state-by-state ballot disqualifications. If Congress somehow passes legislation according to the Court’s guidelines, it could create a system whereby the federal government could challenge President Trump’s and others’ candidacies.

“Anyone who cares about democracy should be grateful for today’s unanimous decision of the United States Supreme Court,” constitutional attorney Gayle Trotter told The Epoch Times.

She said that the “shabby, results-oriented reasoning of the Colorado Supreme Court made it obvious that their decision would not hold up on appeal.”

Heritage Foundation senior legal fellows Hans von Spakovsky and Charles Stimson praised the decision.

“The Supreme Court justices brought order to what could have become a chaotic election season by shutting down this partisan, anti-democratic, and unconstitutional effort in Colorado,” the two said in a press release.

“They found a ‘combination’ of constitutional grounds that ’resolves this case,’ and that explains why the Colorado court got it wrong.”

The Colorado Supreme Court had held that President Trump was not only an “officer” included by Section 3’s language, but also that he engaged in an insurrection—a determination the Supreme Court stayed away from in its per curiam opinion.

Former federal prosecutor Neama Rahmani told The Epoch Times that “the Court gave Trump a win, but only on procedural grounds.”

The court’s three liberal justices—Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown-Jackson—agreed to reject the Colorado Supreme Court decision but, like Ms. Griswold, expressed worry that the court’s opinion would protect insurrectionists.

“[The majority] forecloses judicial enforcement of that provision, such as might occur when a party is prosecuted by an insurrectionist and raises a defense on that score,” their concurring opinion read. They also accused the majority of attempting ”to insulate all alleged insurrectionists from future challenges to their holding federal office.”

Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold (top) supports the Colorado Supreme Court’s (bottom) ruling to disqualify President Trump from the state’s ballot. (Julia Nikhinson/Getty Images, Jeffrey Beall/CC BY 3.0 DEED)

Implications for 2024

At this stage in the election cycle, President Trump continues to face multiple prosecutions that could hinder his ability to campaign or govern if he’s elected in November. Democrats may use that to their advantage but their campaign arsenal took a hefty blow from the Supreme Court’s decision.

“Now that Section 3 has effectively been neutered, all eyes will be on the other constitutional controversies surrounding former President Trump, like the fate of the several pending criminal cases against him and his claims of total immunity from prosecution,” Anastasia Boden, Cato Institute director of the Robert A. Levy center for constitutional studies, told The Epoch Times

The court is scheduled to hear at least two additional arguments related to Jan. 6—including one over whether President Trump enjoys immunity in his D.C. trial.

While this ruling didn’t directly bear on his presidential immunity appeal, it showed an interest in letting Congress respond to the events that day. That’s something President Trump has asked the court to do in arguing that Congress should have to impeach and convict him before prosecutors can pursue him in Article III courts.

Uncertain Path for Congress

The 14th Amendment differs from others in that its text explicitly provides for some kind of congressional authority over its enforcement. Besides Section 5, the last sentence of Section 3 allows Congressional action by removing disqualification by a two-thirds majority.

It’s unclear how future Congresses will attempt to enforce Section 3 but the per curiam opinion suggested it follow two laws. One is the federal insurrection ban (Section 2383), which many have noted wasn’t something President Trump was charged with violating. Another is the Enforcement Act of 1870, which authorizes district attorneys to bring civil actions against federal and state officeholders who violate Section 3.

The Supreme Court is scheduled to hear at least two more arguments related to Jan. 6 – including one over whether President Trump enjoys immunity in his D.C. trial. (Win McNamee/Getty Images, Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

In the immediate aftermath of the Supreme Court’s ruling, elected Democrats appeared reticent. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) both broadly directed attention to the 2024 election.

Former Assistant U.S. Attorney Kevin O’Brien suggested to The Epoch Times that the court was “sketchy” or unclear in how it outlined future congressional action.

“Why does it have to be our Congress, which is partly controlled by one party at a time when that party has put forward a presidential candidate who arguably is an insurrectionist? That’s the real problem … it seems to be favoring Trump in a way that was unnecessary.”

Like the liberal justices, Mr. O’Brien preferred to rule against state action for federal candidates without limiting enforcement to Congress.

The liberal justices’ concurrence saw the main opinion as setting up tension between Section 5 and the last sentence of Section 3.

They wrote: “Section 3 states simply that ‘[n]o person shall’ hold certain positions and offices if they are oathbreaking insurrectionists … Nothing in that unequivocal bar suggests that implementing legislation enacted under Section 5 is “critical” (or, for that matter, what that word means in this context) … In fact, the text cuts the opposite way. Section 3 provides that when an oathbreaking insurrectionist is disqualified, ‘Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.’

“It is hard to understand why the Constitution would require a congressional supermajority to remove a disqualification if a simple majority could nullify Section 3’s operation by repealing or declining to pass implementing legislation.”

Public Interest Legal Foundation President J. Christian Adams, whose organization filed an amicus brief supporting President Trump, told The Epoch Times the liberal justices raised a “legitimate question” about whether a two-thirds majority or simple majority was required to remove disqualification.

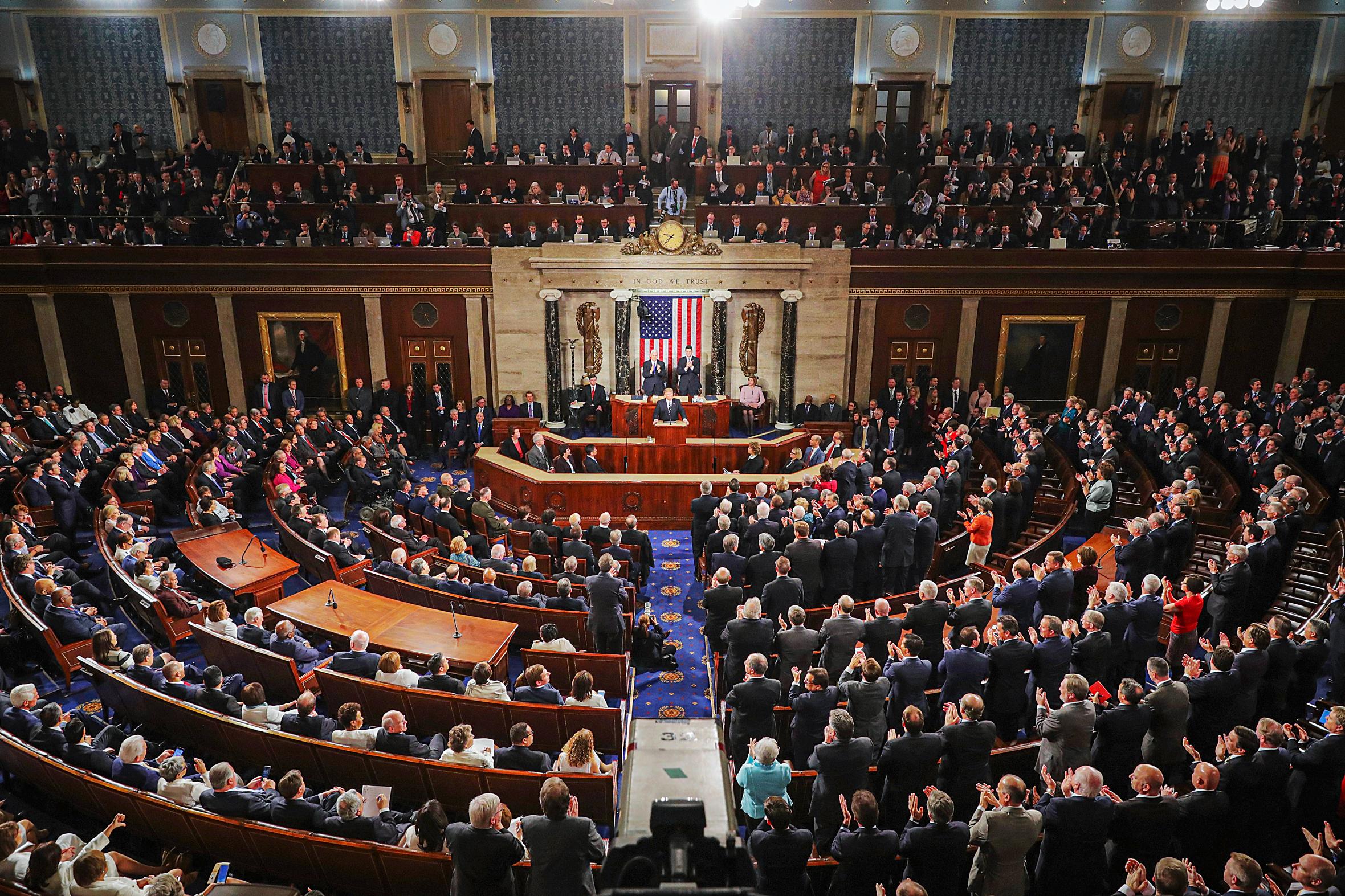

The polarized political environment in Congress substantially lessens the possibility that it will pass anything disqualification-related legislation for President Joe Biden to sign before he leaves office.

The two chambers of Congress, the Senate (top) and the House (bottom), are dominated by different sides of the ideological spectrum. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The two chambers are currently dominated by different sides of the ideological spectrum—continuing the familiar trend of gridlock in Washington. Republicans have more seats in the House but with left-leaning independents, the chamber seems more slanted towards that side of the aisle.

Senate Republican leadership has expressed confidence in the party’s 2024 prospects for that chamber. But if Democrats maintain their majority and retake the House of Representatives, they could turn the weeks before the inauguration into a pressure cooker.

Mr. von Spakovsky suggested Democrats wouldn’t want to “risk” public backlash, while Ms. Boden said Congress was “a dysfunctional branch and this is a very divisive issue, even among [D]emocrats.”

Precedent for Future Disqualification

The Supreme Court’s ruling left a lot on the table, including whether it even applied to former presidents. In some ways, the court’s ruling was representative of the skepticism the justices exhibited during oral argument.

They seemed to focus mostly on the balance of state and federal power but also spent considerable time addressing whether the president was an “officer of the United States” under Section 3.

President Trump spent much of his brief on this question, presumably because it would have removed him from inclusion in the language’s meaning.

“There is no jurisprudence out there of any significance as to what is an officer of the United States,” Mr. Adams said. “So they would have been building the edifice from the ground up jurisprudentially.”

Even if Congress did pass a law enforcing Section 3, Mr. von Spakovsky said it was possible that another candidate like President Trump could re-raise the “officer” issue with the Supreme Court.

In setting its guidelines, the majority referred to the court’s 1997 decision in City of Boerne v. Flores, which involved a dispute over permitting for a church in Texas.

“Any congressional legislation enforcing Section 3 must, like the Enforcement Act of 1870 and §2383, reflect ‘congruence and proportionality’” between preventing or remedying that conduct and the means adopted to that end,” the March 4 opinion read.

Original News Source Link – Epoch Times

Running For Office? Conservative Campaign Consulting – Election Day Strategies!