Migrants in Mexico have made more than 64.3 million requests to enter the U.S. using a smartphone app that the Biden administration has tried to establish as the main gateway to the American asylum system at the southern border, internal federal government documents obtained by CBS News show.

In the first year of the program’s implementation, migrants used the phone app, known as CBP One, tens of millions of times to apply for a coveted appointment to be processed by U.S. immigration authorities at an official border crossing, according to the internal documents. So far, nearly 450,000 migrants have been allowed into the U.S. under the process, the documents show.

The documents cover a 13-month period between January 2023, when the Biden administration started allowing migrants to request appointments using CBP One, and Feb. 8, 2024. On average, migrants have made just under 5 million appointment requests per month.

The number of requests does not represent unique individuals, since the total includes repeated attempts by the same people. Nonetheless, the figure illustrates the extraordinarily high demand among migrants to come to the U.S. and the desperation that leads many to try again and again to secure a chance to enter the country.

“It’s a staggering number,” said Theresa Cardinal Brown, a former U.S. immigration official during the administrations of Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama. “There’s a lot of people who would love to migrate to the United States. In essence, they see CBP One as sort of a self-petitioning mechanism that we’ve never had before.”

A Biden effort to control migration

The Biden administration has sought to use the CBP One system to encourage migrants to refrain from crossing the border illegally in between ports of entry. Unlike those who enter the country unlawfully, migrants who secure a CBP One appointment can apply for a work permit after being released from U.S. custody and do not have to satisfy the stricter asylum conditions of a Biden administration regulation.

That rule presumes migrants are ineligible for asylum if they enter the U.S. unlawfully after failing to seek refuge in a third country, like Mexico, on their way to American soil.

As of Feb. 8, U.S. officials at ports of entry along the southern border had allowed 448,701 migrants with CBP One appointments to enter the country, giving them notices to appear in immigration court to plead their cases, according to the internal government documents.

The top origin countries of those allowed into the U.S. under the program, the documents show, are Venezuela, Mexico, Haiti, Cuba, Honduras, Russia, El Salvador, Colombia, Chile and Guatemala.

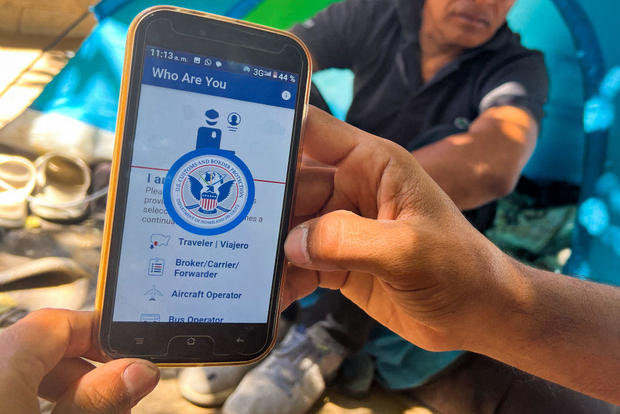

The CBP One process is available in English, Spanish, Haitian Creole, Portuguese and Russian, and open to migrants from any country who are physically in central or northern Mexico. A geofencing feature is supposed to block anyone south of Mexico City from using the app.

Every morning, the U.S. government distributes 1,450 new CBP One appointments. Most of them are allocated randomly, while 30% of them are offered to migrants who have been waiting in Mexico the longest. Those who fail to get an appointment have to try again the next day.

A senior U.S. Customs and Border Protection official said the number of CBP One appointment requests is “high,” but “not unreasonably high.” Migrants are often making a new request each day until they get an appointment, according to the official, who requested anonymity to discuss the process.

“If somebody requests for five weeks straight before they get an appointment, that individual is showing up 35 times in that number,” the senior CBP official told CBS News.

While the agency increased the daily number of CBP One spots several times last year, the official said there are no current plans to do so again. The official noted that together with dozens of humanitarian exemptions to the CBP One requirement, the U.S. is processing more than 1,500 migrants each day at ports of entry — four times the pre-pandemic level.

Mixed results with CBP One

The CBP One system is one of several programs the Biden administration has established to give migrants a legal and orderly way to come to the U.S., alongside an initiative that allows Americans to sponsor the entry of up to 30,000 Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans each month. Those processes have been paired with a rule that restricts asylum eligibility and expands deportations.

While the administration credited this “carrots and sticks” strategy for a two-year low in illegal border crossings in June 2023, migrant crossings in between ports of entry later spiked, reaching a quarter of a million in December, a record high.

The impact of the CBP One process has also varied widely by nationality. Illegal border crossings by Cubans and Haitians, two of the top nationalities using CBP One, have remained very low compared to 2022 and 2021. On the other hand, tens of thousands of migrants from Central America and Venezuela have continued to cross into the U.S. unlawfully each month, bypassing the CBP One system.

The senior CBP official attributed the disparate impact to the large diaspora communities that help migrants from Cuba and Haiti and provide them information about U.S. border policies.

Cardinal Brown, the former U.S. immigration official who now serves as a senior adviser at the Bipartisan Policy Center, said the CBP One system is “providing some order” at the border. But she said many migrants are also giving up waiting for appointments and crossing into the U.S. without authorization.

The incentive to wait for an appointment has been diluted by the fact that many migrants who enter the country illegally are still released with court notices. Due to insufficient detention facilities and asylum officers, the government has been releasing most migrants who cross the border illegally over the past several months, instead of screening them using the heightened asylum standards, government data show.

The number of CBP One appointments, Cardinal Brown added, is “clearly a drop in the bucket of this massive number of migrants moving in this hemisphere and trying to get to the United States.”