Washington — The Supreme Court on Tuesday appeared inclined to side with the Food and Drug Administration in a case involving a commonly used abortion pill and recent agency actions that made the medication easier to obtain, as the justices raised questions about whether a group of doctors challenging the moves demonstrated they had the proper basis to sue in federal court.

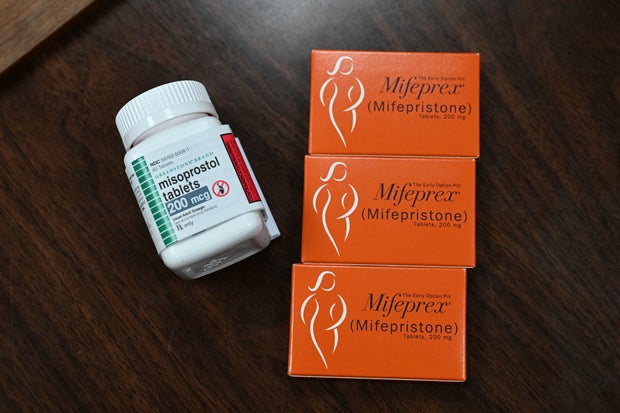

At the center of the legal battle is the pill mifepristone, which is taken along with another drug to terminate an early pregnancy. Approved by the FDA in 2000, more than 5 million patients have taken mifepristone, according to the agency, and studies cited in court filings have shown it is safe and effective.

In 2016 and 2021, the FDA took steps to make mifepristone more accessible, including allowing it to be taken later into a pregnancy and delivered through the mail without an in-person doctor’s visit. A group of anti-abortion rights doctors and medical associations challenged those changes, claiming the FDA violated the law.

The Supreme Court is now reviewing a decision from a federal appeals court that found the agency’s actions were unlawful. A ruling in the case, known as FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, that unwinds those changes would threaten to curtail access to mifepristone nationwide, even in states with laws protecting abortion access.

Oral arguments

Rolling back the FDA’s actions would “inflict grave harm on women across the nation,” Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar told the court. She reiterated that the ruling from the lower court marks the first time any court has restricted access to a FDA-approved drug by second-guessing its judgment about the conditions required to ensure its safety.

The justices focused most of their questions on whether the doctors who filed the lawsuit against the FDA had shown that they may be injured by its actions, and whether those alleged injuries could be traced to the FDA’s easing of the rules. If the court decides that the doctors do not have legal standing to sue, it could order the case dismissed without deciding whether the FDA acted lawfully when it relaxed the requirements for obtaining mifepristone.

In one exchange with Erin Hawley, a lawyer with the Alliance Defending Freedom who represented the medical associations and doctors, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said there is an “infinitesimally small” chance that a pregnant woman who may need medical attention after taking mifepristone would end up in a hospital where one of the member physicians is working.

Hawley pointed the justices to declarations from two doctors, filed in an earlier stage in the case, that she said showed they had been complicit in terminating a pregnancy for a patient who experienced complications from a medication abortion. But Justice Amy Coney Barrett pushed back, and said it didn’t appear that either doctor actually participated in the procedure.

Justices Neil Gorsuch and Ketanji Brown Jackson indicated they struggled with the scope of the decisions from lower courts that rolled back the FDA’s 2016 and 2021 changes nationwide.

“Recently … we’ve had one might call it a rash of universal injunctions,” Gorsuch said, adding “this case seems like a prime example of turning what could be a small lawsuit into a nationwide, legislative assembly on an FDA rule.”

Chief Justice John Roberts questioned why the courts couldn’t provide narrow relief that applied only to the doctors involved in the lawsuit, as opposed to targeting the FDA more broadly.

Access to mifepristone has remained unchanged while legal proceedings in the case have continued, since the high court issued an order last April preserving its availability. That relief will remain in place until the Supreme Court hands down its decision, expected by the end of June.

Arguments in the case are took place less than two years after the Supreme Court ruled in June 2022 to unwind the constitutional right to abortion and return the issue to the states. It also comes on the heels of new findings that medication abortions in the U.S. have risen since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

A study published Monday in the medical journal JAMA found that the number of self-managed abortions obtained using pills grew in the six months after the high court reversed Roe. Research from the Guttmacher Institute, an organization that supports abortion rights, published last week showed that medication abortions accounted for 63% of all abortions that took place within the U.S. health care system in 2023, up from 53% in 2020.

The dispute over mifepristone

The challenge to the FDA’s efforts surrounding mifepristone was filed in November 2022 — more than two decades after the drug was made available in the U.S. — by a group of medical associations that oppose abortion rights. Brought in federal district court in Texas, the groups, led by the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, challenged the FDA’s initial 2000 approval and its more recent changes in 2016 and 2021.

As part of those actions, the FDA allowed mifepristone to be taken up to 10 weeks into a pregnancy, instead of seven weeks, reduced the number of in-person visits required from three to one, allowed more health care providers to prescribe the drug and lifted a requirement that it be prescribed in-person.

The organizations claimed the FDA did not have the authority to approve mifepristone for sale and failed to adequately consider the drug’s safety and effectiveness.

The federal judge overseeing the case, U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, agreed that the FDA’s 2000 approval and subsequent actions were likely unlawful. He blocked the FDA’s initial action allowing the drug to be sold in the U.S.

But Kacsmaryk put his ruling on hold, and a federal appeals court and the Supreme Court intervened. The high court ultimately maintained access to mifepristone while legal proceedings continued.

Months later, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit upheld the FDA’s 2000 approval of the abortion pill, but said the agency violated the law with its more recent changes. The appeals court’s decision, though, is preempted by the Supreme Court’s earlier April 2023 order protecting access.

The Justice Department and Danco Laboratories — the maker of Mifeprex, the brand-name version of mifepristone — asked the Supreme Court to review the 5th Circuit’s ruling, and it agreed to do so in December.

The legal issues in the case

In asking the justices to reverse the appeals court’s decision, the Biden administration has argued that the medical associations and their physician members do not have legal standing to sue. The doctors do not prescribe the drug and haven’t identified a single case where a member has been forced to complete an abortion for a woman who shows up at an emergency room with an ongoing pregnancy, Prelogar said.

“They stand at a far distance from the upstream regulatory action they’re challenging,” she said of the anti-abortion rights physicians, and argued the theories they raise are “too attenuated as a matter of law — the court should say so and put an end to this case.”

Many of the questions the justices asked Prelogar focused on the question of standing. “Shouldn’t somebody be able to challenge that in court? Who? Who would have standing to bring that suit?” Justice Samuel Alito asked.

He claimed that the argument advanced by the Biden administration indicates that even if the FDA violated the law, nobody has the proper basis to sue.

“There’s no remedy, the American people have no remedy for that,” said Alito, who authored the Supreme Court’s majority opinion overturning Roe.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh sought to confirm that under federal law, doctors cannot be forced to violate their conscience to perform or assist in an abortion. Prelogar said federal conscience protections provide broad coverage for doctors in that circumstance.

But lawyers for the medical groups, represented by the Alliance Defending Freedom, argue that their members object not only to abortion, but also to “complicity in the process.”

“FDA has spent decades directing women harmed by abortion drugs to emergency rooms. Many of them have sought treatment from respondent doctors,” the lawyers wrote in a brief to the court. “Now that FDA is called to account for the harm caused, the agency cannot insist that the very treatment option it directed is somehow speculative.”

If the Supreme Court agrees with the Justice Department that the doctors do not have the proper basis to sue in federal court, it would order the case dismissed without deciding whether the FDA acted within the bounds of the law.

But if the justices reach the legal issues raised in the case, the Justice Department and Danco have urged the court to find that the FDA’s 2016 and 2021 actions were lawful.

The agency relied on a “voluminous body of medical evidence” on mifepristone’s use over decades when it determined that the 2016 changes would be safe, Prelogar wrote in her own brief. In any event, the district court was wrong to second-guess the determinations that Congress empowered the FDA to make, she said.

“To the government’s knowledge, this case marks the first time any court has restricted access to an FDA-approved drug by second-guessing FDA’s expert judgment about the conditions required to assure that drug’s safe use,” Prelogar wrote.

Pharmaceutical companies and former heads of the FDA have warned the court that a decision upholding the 5th Circuit threatens to undermine the agency’s drug-approval process and could lead to persistent legal challenges of its approval decisions.

The lower court’s approach, if left intact, “would allow courts to substitute their lay analysis for FDA’s scientific expertise and to overturn the agency’s approval and conditions of use for drugs — even after they have been on the market for decades,” a group of former commissioners and acting commissioners told the court in a brief.

“The resulting uncertainty would threaten the incentives for drug companies to undertake the time-consuming and costly investment required to develop new drugs and ultimately hinder patients’ access to critical remedies that prevent suffering and save lives,” they said.

A slew of pharmaceutical companies and executives separately stressed the importance of drug companies being able to rely on the courts to respect the FDA’s scientific judgements.

“If a court can overturn those judgments many years later through a process devoid of scientific rigor, the resulting uncertainty will create intolerable risks and undermine the incentives for investment regardless of the drug at issue,” they said in a brief. “This, in turn, will ultimately hurt patients.”

But lawyers for the medical associations and their members that oppose abortion rights argued that the FDA failed to give a “satisfactory explanation” for its decision to lift the in-person dispensing requirement and called the studies the agency relied on “deeply problematic.”

Withdrawing the in-person visit requirement in 2021 eliminated the opportunity for health care workers to screen for ectopic pregnancies and other conditions, the associations argued. In 2016, the FDA removed “interrelated safeguards without studies” that examined the changes as a whole, they continued.

The group Americans United for Life, which is backing the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, claimed that the FDA has promoted access to abortion pills without medical supervision, which have increased health and safety risks to women and interfered with their care.